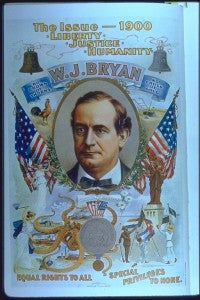

Title: “The Drunkard’s Progress,” 1846

About the image: Step 1: A glass with a friend. Step 2: A glass to keep the cold out. Step 3: A glass too much (weaving). Step 4: Drunk and riotous (policeman with club”). Step 5: The summit attained…Jolly companions…A confirmed drunkard. Step 6: Poverty and Disease (with cane). Step 7: Forsaken by Friends. Step 8: Desperation and crime (with gun). Step 9: Death by suicide.” Early 19th century Temperance painting. Fear, laced with appeals to the conscience, was the main weapon of temperance leaders of this period and later who endeavored to make Americans forswear the bottle. The rise of social disorder, with burgeoning slums, impoverished families, increases in crime, prostitution and Sabbath-breaking, was seen by many as the result of drink. Aside from the penitentiary and its supposed influence through fear, another means of crime prevention was the temperance movement. “Drink is the cause: stop crime and poverty at their source.” Temperance tales paint the drinker as not only immoral and sinful but also unsuccessful: the drunkard loses devotion to work, his reputation for reliability, and his job.

Why does American River College faculty member, Camille Leonhardt, find this image interesting?

Images of the Drunkard’s Progress are very useful in helping students to understand the Temperance Movement of the nineteenth-century. The Temperance Movement arose within the broader context of economic and geographic transformations underway. Alcohol consumption increased dramatically during the early nineteenth-century, with distilled liquor consumption peaking in the early 1830s. The Drunkard’s Progress image serves as a useful tool for beginning to explore these trends during the era. Why were Americans drinking more distilled liquor? (Cultural changes underway and increased anxiety). Why did they have access to more distilled liquor? (Physical expansion and the ease of transporting a concentrated form of their crops, such as grains and barley).

The image also serves as a very useful tool for exploring how Americans sought to establish order within a period of cultural and economic change. The two-pronged strategy pursued by temperance societies reveals how Americans sought to establish social order by imposing legal sanctions prohibiting the sale and manufacture of liquor, in addition to encouraging individuals to take oaths of abstinence. Advocates of temperance signed pledges to abstain from liquor consumption. Temperance advocates achieved a legal victory in Maine in 1851, with passage of the first statewide prohibition statute.

Participation in the Temperance Movement proved to be very validating for women and provided many women with opportunities to develop skills and confidence needed to demand political rights of their own. Established in 1874, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, WCTU, became one of the largest female organizations in the United States. Even before the formation of the WCTU, other temperance societies provided women with the rare opportunity to participate in meetings, plan strategies, and gain experience with leadership.

View more temperance images from before 1870 here.

Related Topics/Themed Collections: Nineteenth Century, Liquor, Temperance to 1870′s

Lessons in the Marchand Collection:

- Northern Reform Communities Town Hall Meeting by Jeff Pollard, CHSS 8.6 & 8.9, IN PRINT – AVAILABLE IN THE MARCHAND ROOM

Related Resources Available in the Marchand Collection:

- Susan Leighow, Rita Sterner-Hine, The Antebellum Women’s Movement, 1820 to 1860: A Unit of Study for Grades 8-11,Organization of American Historians and the Regents, University of California, 1998.

- Elisabeth Griffith, In Her own Right: The Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, New York: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Share your ideas! How would you use this image?

Click here to let us know.