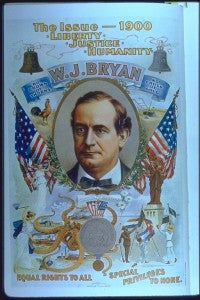

Image title: “Chicago Day at the Exposition,” 1893

Today, if you were to visit the site where, on October 9, 1893, more than 751,000 people visited the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, you would find a tranquil city park with a massive museum at its north end.

The crowd amassed on Chicago Day included more people than had ever gathered for any peace-time event in the known history of the world. According to Erik Larson, “the [Chicago] Tribune argued that the only greater gathering was the massing of Xerxes’ army of over five million souls in the fifth century B.C.”

They had come to see the White City, a city built in south Chicago’s Jackson Park and built specifically for the Columbian Exposition. The buildings were temporary structures, but their neo-classical design, the boulevards that ran between them, the dredged and re-configured Jackson Park, and the civic spirit that made it possible to build the Exposition in less than three years all left their permanent mark on the city of Chicago.

In January 2012, I visited Chicago to attend the American Historical Association’s annual meeting. I finished reading Erik Larson’s Devil in the White City just days before my trip, so while I was in the Windy City I visited Jackson Park. The Palace of Fine Arts (reinforced with stone in the late 1920s and now Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry) is all that remains of the White City. The Japanese Garden on Wooded Island stands as the only visible trace of landscaping. Frederick Law Olmsted’s radical designs grew as he intended: so that future visitors would not be able to detect the changes he made. The rest of Jackson Park appears as though it has always looked as it does now.

So the image “Chicago Day at the Exposition” is important because it shows just how radically Daniel Burnham, Frederick Law Olmsted, and others changed the face of Jackson Park and Chicago. Without photographs from the 1893 Columbian Exposition, it is difficult to imagine the scale of the spectacle. It is difficult to get a sense of the majesty of the event at which Juicy Fruit, Pabst Blue Ribbon, Cracker Jack, Shredded Wheat, Aunt Jemima’s pancakes, and the Ferris wheel all made their debut.

Further Reading:

1. Theodore Dreiser, Sister Carrie (New York: B. W. Dodge, 1907).

2. Erik Larson, The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America, 1st ed. (New York: Crown Publishers, 2003).

3. Carl Smith, “Where All the Trains Ran: Chicago,” Common-Place 3, no. 4 (July 2003), http://www.common-place.org/vol-03/no-04/chicago/.

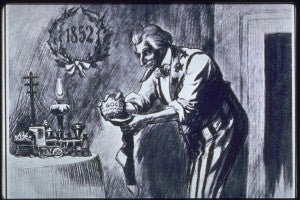

About the image: Poster, “Destroy This Mad Brute…ENLIST if you want to fight for your country…If this war is not fought to a finish in Europe, it will be on the soil of the United States,” 1917. Ad, U.S. Army, World War I. Kaiser Wilhelm II has been turned into a huge, black, insane ape wearing a German spiked helmet labeled “Militarism,” abducting a terrified Columbia for rape, bringing down a bloodied club labeled “KULTUR” on “AMERICA,” and threatening the next victim, the viewer. Blood drenches his hands and wrists. This slobbering beast personifies several other stereotypes, racial ones included. H.R. Hopps poster.

About the image: Poster, “Destroy This Mad Brute…ENLIST if you want to fight for your country…If this war is not fought to a finish in Europe, it will be on the soil of the United States,” 1917. Ad, U.S. Army, World War I. Kaiser Wilhelm II has been turned into a huge, black, insane ape wearing a German spiked helmet labeled “Militarism,” abducting a terrified Columbia for rape, bringing down a bloodied club labeled “KULTUR” on “AMERICA,” and threatening the next victim, the viewer. Blood drenches his hands and wrists. This slobbering beast personifies several other stereotypes, racial ones included. H.R. Hopps poster.