From the Culture of Character to the Culture of Personality

Bradley and the "Culture of Personality" click on image to see full version

Douglas and the "Culture of Character" click on image to see full version

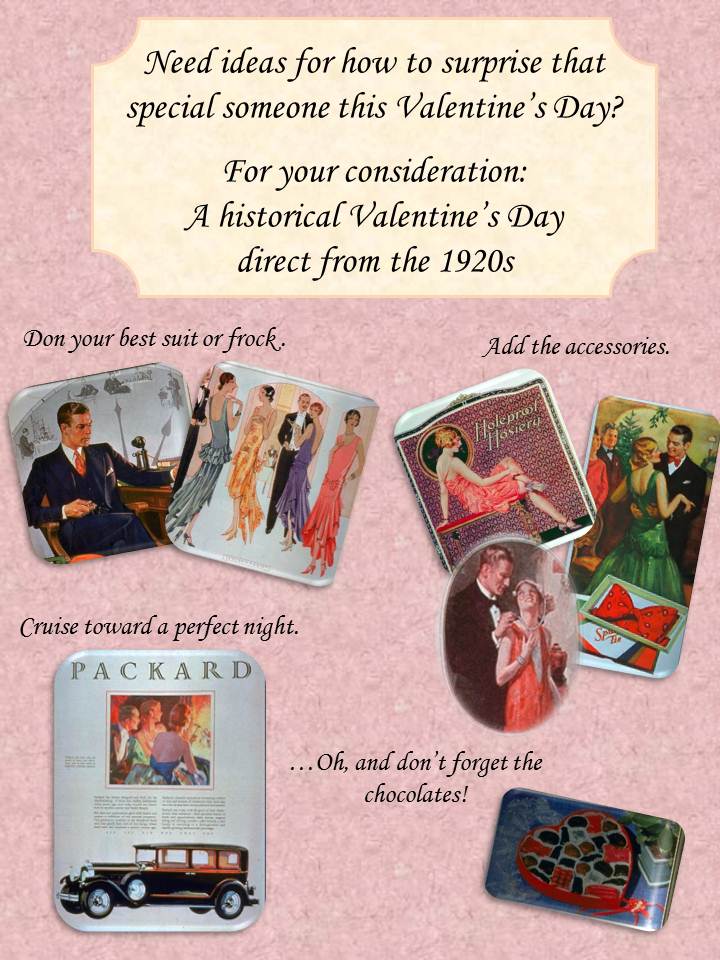

Commentary from Tim Yates, former History Project staff member: The Marchand Collection offers a wealth of images that can be used in the classroom to illustrate and prompt discussion of what cultural historians mean when they abstractly describe the shift from a inner-directed nineteenth-century culture of character to an other-directed twentieth-century culture of personality. The socioeconomic causes of this shift also involved other abstract historical concepts such as the shift from producerism to consumerism, for which the Marchand Collection also provides useful illustrations beyond the ads discussed in this post. While Douglas and Bradley are both products of the longstanding American emphasis on self-improvement, they are different historical types. Douglas represents the successful inner-directed producer come industrialist who helped Americans overcome scarcity through factory production. Expanding factory operations enabled the kind of industrial mass-production pioneered by Henry Ford in the early twentieth century. The productivity of nineteenth-century middle-class men such as Douglas led to the emergence after 1900 of middle-class men such as Bradley, who increasingly found themselves selling mass-produced goods or doing other kinds of white-collar work in the office environments of large corporations or public bureaucracies. Success in many of the jobs created by mass production and consumption required other-directed management of social impressions. Advertisers and self-improvement promoters offered twentieth-century self-makers a range of new solutions for the changing circumstances, solutions that centered on personality enhancement. Explore the Marchand collection for examples of advertising appeals to personality enhancement as well as images depicting the rise of mass production. This chapter of American history raises other historical questions that the Marchand Collection might help elucidate. How did middle-class American women experience of the cultural shift from character to personality and the underlying shift from a producer-oriented to a consumption-oriented economy? When and how did working-class and ethnic-minority groups experience this new twentieth-century culture? How did the rise of a mass-production and mass-consumption economy shape American politics over the course of the twentieth century? How does the nineteenth-century emphasis on character influence our society today? How does the more recent culture of personality influence your life?

MORE ABOUT THE IMAGES

Douglas and the Culture of Character: This advertisement for W.L. Douglas shoes vividly illustrates popular nineteenth-century American ideas about manhood and success. The ad promotes W.L. Douglas shoes in an appeal emphasizing the qualities of Douglas the shoemaker, a self-made man sincerely dedicated to the craft he began learning it as a young child. Cultural historian Warren Susman has argued that nineteenth-century America “was a culture of character” rooted in “producer values” that idealized thrift, discipline, work, morality, duty, citizenship, and reputation. Americans considered these qualities prerequisites for true success. Douglas has these qualities. He contrasts both the nineteenth-century drunkard who weakly squandered money and became a slave to alcohol, and the confidence man, who spent his energies in criminal schemes hinging on the cultivation of false social impressions. Douglas is a hard-working man who has achieved self-mastery by directing his energies inward to develop discipline. He frequently spends his days in Boston thriftily purchasing his own supplies to eliminate the middleman costs, which, the ad assures readers, his stores do as well. Upon returning from Boston, he often works alone late into the night. Relentlessly efficient and productive, Douglas is a sincere man of character, and character translates into affordable shoes with quality.

“Bradley” and the Culture of Personality: This 1922 ad for “Nerve,” a series of six pocket-sized self-improvement courses created by William G. Clifford and promoted by Fairfield Publishers, Inc., offers a new narrative of success, one that differs from the W.L. Douglas shoe ad in historically important ways. Here the individual–a man named Bradley–is subjected to a new set of psychological demands for self-mastery conveying a new model of success. In this ad the language of character has been replaced with the new language of what Susman identifies as emerging culture of “personality,” which generated new models of success and manhood emphasizing self-confidence, self-realization, and self-gratification, and celebrating the kinds of impression manipulation that formerly signaled the immorality of the nineteenth-century confidence man. The ad informs readers that Bradley, who once lacked self-confidence and a sense of self-worth, has become a man whose “vividness and charm” magnetically attract “favorable attention,” and a man consequently awarded with a $12,000-a-year job. Whereas the Douglas ad featured imagery of individual productivity, this ad shows Bradley walking into a room and commanding favorable attention. Bradley is a success because he is well-liked and charming. His self-improvement bears little or no resemblance to Douglas’s thrift, hard work, and long-honed skills at producing a purchasable good. Instead, Bradley is a success because he has “gain[ed] the self-assurance that strongly impresses people,” “overcome nervousness,” developed “an impressive and winning personality,” and mastered the ability to “deal with ‘big’ people as easily” as easily as he interacts with “his closest friends” by learning to “dominate and control” both “business and personal conditions.”

SUGGESTED READING:

Karen Halttunen, Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle Class Culture, 1830-1870.

Jackson Lears, Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertising in America.

Roland Marchand, Advertising and the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920-1940.

Warren Susman, Culture as History: The Transformation of American Society in the Twentieth Century (see especially “Personality and the Making of Twentieth-Century Culture,” pgs. 271-285).

Timothy (Tim) Yates received his Ph.D. in U.S. History in 2007 from U.C. Davis, where he worked for the History Project as a digitizer of images from Roland Marchand’s and Karen Halttunen’s teaching collections, a research assistant for summer programs, and a Teaching American History grant contributor. Tim currently works as a consultant for ICF International analyzing the history of built environments for development projects requiring federal and/or state regulatory compliance. Tim’s most notable recent work for ICF has consisted of researching and writing histories of National Historic Landmark sites and resources such as Mission San Gabriel and the Doyle Drive and Veterans Boulevard Highway Exchange (the south approach roads to the Golden Gate Bridge).