Women’s Rights Movement series, part 5

This past week we’ve delved into the various aspects of the early Women’s Rights Movement. Today, Debra Schneider, social studies teacher at Merrill F. West High School, provides us with her expertise and hands on experience for teaching this subject in the classroom. Click here for more from Debra Schneider.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

For years, I have taught a unit on social movements of the 20th century in my 11th grade US History course, primarily focusing on the African American civil rights movement. Our focus is to explore issues at stake and strategies for gaining civil rights. This makes it easy to shift focus to any other social movement of interest to my students, such as the disability rights movement, the Chicano Youth movement, the marriage equality movement and others, continuing to explore issues and strategies. One problem: so many movements, so little time!

Then, a few years ago, after attending a fantastic Gilder-Lehrman Teacher Seminar on women’s history designed by Nancy Cott at The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, I made the commitment to always include the women’s movements of the 20th century in the social movements we study. In addition to making sure women are part of our study of the Progressive era, the Great Depression, America at war, and other time periods, I have collected and created a series of lessons to study “two waves” of feminism.

I start by accessing students’ prior knowledge of the role of women with the concept of separate spheres: the “private sphere” of women and the “public sphere” of men. I admit I am quite dramatic and exaggerate these to set up a sharp dichotomy between the two, but later use images of women at work to show the myths in this ideology. I also introduce the idea of two waves of feminism that have tried to change this ideology, with the expectation that we’ll evaluate how far we have come at the end of the unit.

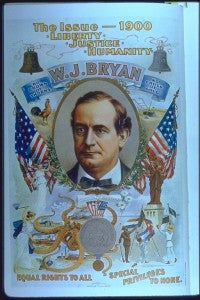

We use the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments as our baseline to see what women’s role in society was in the mid-1800s and to start our study of suffrage. We explore a set of images I have collected that show arguments for and against suffrage, including political cartoons, broadsides, and some anti-suffrage documents from the Stanford History Education Group. Students usually understand the pro-suffrage arguments easily, so we spend more time on the anti-suffrage movement. Students are shocked to learn that many anti-suffragists were women! Students learn about the 19th Amendment, but see that there were still more rights to be gained.

Ad: Pictorial Review, “The CHANGE that has come to WOMAN” 1931.

Next we move on to the changing role of women through the 20th century. For this, I use a great set of resources created by Carolynn Ranch for the UC Davis History Project showing women through from the 1940s to the 1990s with advertisements, song lyrics, primary source expository texts, biographical sketches, and depictions of television show characters. Groups of students study and discuss each decades’ sources and use them to decide: How are women depicted in this decade? Before the lesson, they usually hypothesize that women will have more and more freedom and rights over time. After the lesson, they are surprised to find that women’s rights and freedoms seemed higher in the 1940s than in the 1950s, for example. Here’s where they come to see that gender roles are often constructed by the nation to fill its changing needs.

Next we study the women’s liberation movement of the mid-century, starting with excerpts from Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. Many students are aware of this wave of feminism and hope to enjoy its benefits, but there is often a lot of nostalgia for “the good old days,” so I also introduce the ideas of Stephanie Coontz’s The Way We Never Were.

Most of my students think that the goal of the mid-century women’s movement was to encourage all women to move into the world of paid work, and perhaps with some parity with men (because this is the observed experience of many of them). My purpose in this lesson is to have them discover the complexity of the feminist movements, their intersectionality, and to see that women had conflicting and multiple ideas about what women’s problems were and how best to address them. I use documents expressing differences among racial/ethnic groups to illustrate the conflicts.

The last activity is a scored class discussion that asks, “How fair and equal is life for women in America today?” We discuss three topics: employment and wages, education, and political participation. Students use the Seneca Falls Declaration, everything we’ve learned so far, and a fact sheet on women in the US today as their sources. This has never failed to create a lively discussion with well-supported arguments that usually lasts two class periods.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The complete Women’s Rights Movement series includes posts on: the early movement, bloomers, anti-suffrage cartoons, and the 19th Amendment. Join us next week for another Women’s History series!