Title: The Holy Family at Work

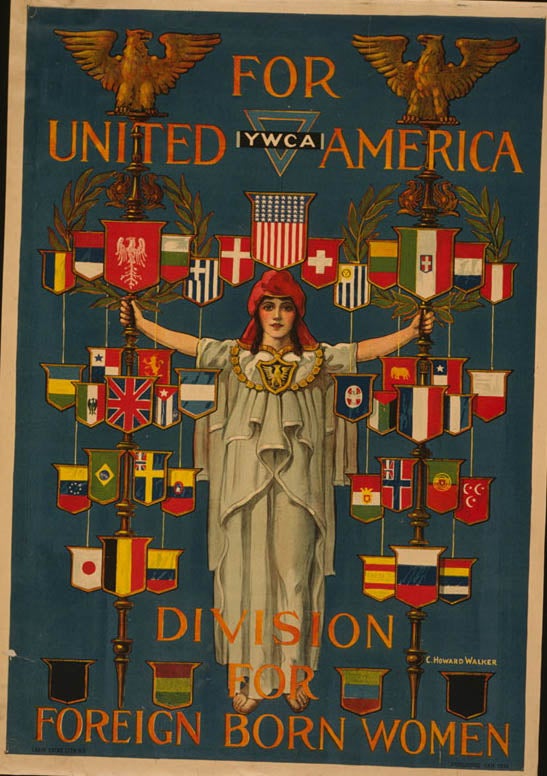

The Holy Family at Work. From the Book of Hours of Catherine of Clèves

Here’s what Shennan Hutton, author of Women and Economic Activities in Late Medieval Ghent, had to say about this image:

This image of the “Holy Family at Work” comes from the book of hours of Catherine of Clèves. One of my favorite medieval visuals, it depicts the Virgin Mary, Joseph, and the toddler Jesus. Mary is weaving, Joseph is working wood, and Jesus is toddling around in his wooden walker. The ribbon extending upwards from his mouth is the medieval equivalent of a “thought bubble.” It reads, “This is my beloved mother.” Although groupings of the Holy Family was a popular theme in medieval art, it is a bit unusual to see the adults at work. In typical medieval fashion, Mary, Joseph and Jesus appear dressed in burgher clothing (like the urban workers Catherine of Clèves might have glimpsed as she shopped in one of the cities of her tiny principality.) Either her father or her husband commissioned this book of hours for Duchess Catherine of Clèves, as a wedding gift for her marriage to Duke Arnold of Guelders.

Clèves was a tiny county in the Low Countries, to the east of Flanders, north of France, and on the western edge of the Holy Roman Empire. Today part of it is in Germany and part in the Netherlands. Guelders was another small principality, entirely within the Netherlands today. In the Late Middle Ages, books of hours were prized possessions of wealthy nobles and urban elites. Many books of hours were made by artisans in the Low Countries, modern-day Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. An unknown artist (probably several artists in a workshop) in Utrecht (the Netherlands) completed this one for Catherine in 1440. The Book of Hours contained little prayers to be said at certain hours of the day, hence the term “hours.” Most of the pages were decorated with brightly painted illustrations, sometimes called illuminations or miniatures, of portraits of saints, visions of hell, and scenes from Jesus’s life, all drawn by hand. Production and consumption of these books served many functions. Owners displayed their books of hours as a sign of wealth, but also used the books for private religious meditation in their homes. Often the books were decorated with the coat of arms of the owner intertwining with religious symbolism. For this reason, books of hours exemplify the fourteenth- and fifteenth-century movement called the “laicization of spirituality,” a time when lay people were increasingly practicing their faith outside of the church setting, without the mediation of a clergyman. This was an important precursor to the Reformation. At the same time, this image depicts a very pre-Reformation subject, complete with an aged Joseph (medieval people usually thought of Joseph as an old man) and halos of sainthood. I like to use this image to show how rich nobles and elites displayed their family background and prestige, and how spiritual practices were moving out of the church into private spaces. However, this image is most useful for its unique background. Although only the wealthiest people could afford to purchase books of hours, this image does not show the interior of a lavish townhouse or rich castle. The room surrounding the Holy Family is the main room of a house that might have been owned by a late medieval burgher (a solid urban citizen.) It is the kind of house that the artist might have lived in. This little illumination might even have been drawn by a woman. In fifteenth-century Bruges (just to southwest of Utrecht), there was a guild for artists who drew illuminations. One of every four members of this guild was a woman. Whether or not the artist was a woman, she or he drew a scene from daily life to surround the Holy Family. As such, it gives us a fascinating glimpse into daily life in the Late Middle Ages.

You can see more images from the Book of Hours of Catherine of Clèves here.

Shennan Hutton is a Program Coordinator for the California History Social Science Project. She taught world history in high school for 15 years, before entering the graduate program at UC Davis. She earned a Ph.D. in medieval European history in 2006. She teaches medieval, European and world history at various colleges and universities, as well as promoting K-16 collaboration at the California History-Social Science Project. You can read more from Shennan at Blueprint for History Education.